When you get ready to paint something, you look at your blank canvas, or wall, pick up a paintbrush and grab a color or two. Simple, right?

When you get ready to paint something, you look at your blank canvas, or wall, pick up a paintbrush and grab a color or two. Simple, right?

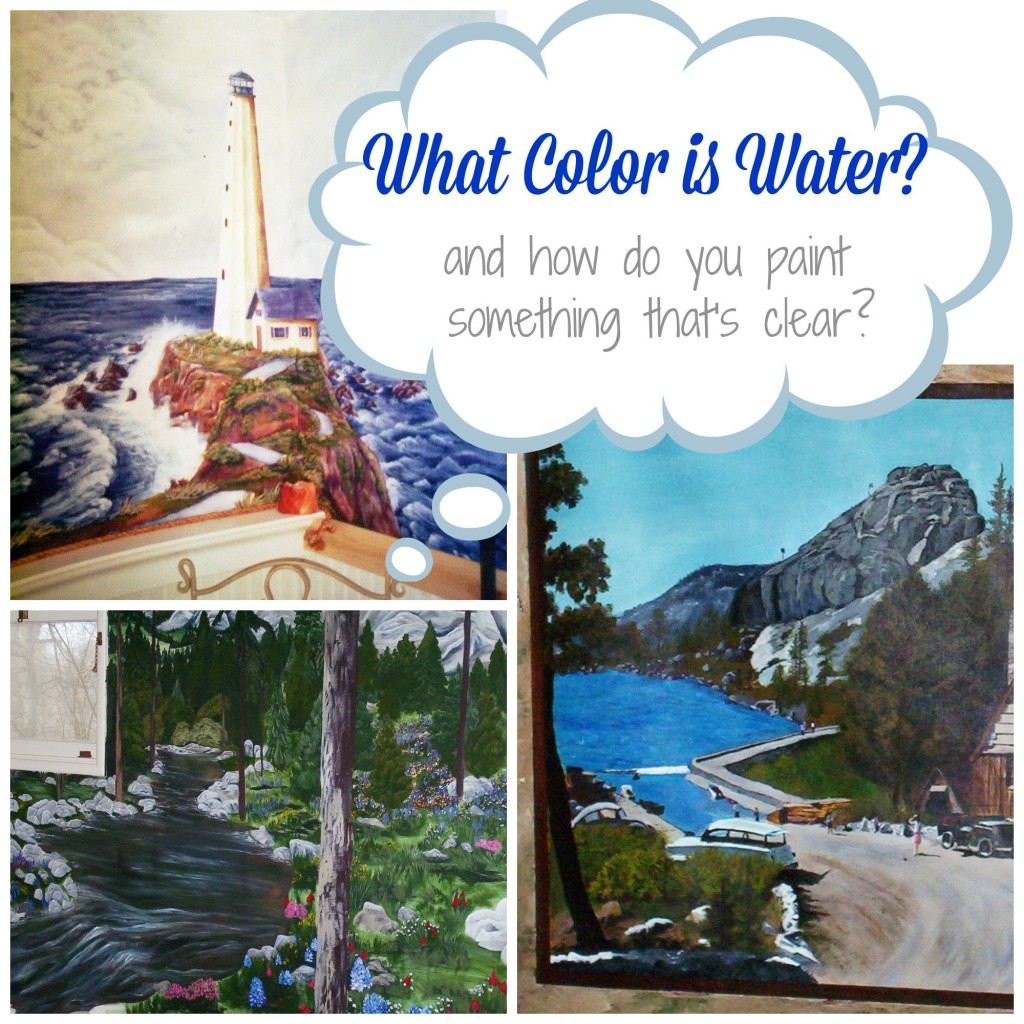

But how do you paint something that inherently has no color, as in clear water?

If you give a child a paintbrush and some paint and tell her to paint water, she will, without hesitation, cover the paper with a swath of blue.

Fast forward 30 years or so, to when said child picks up a paintbrush to paint her family’s resort that sits at the edge of a glacial lake, and the canvas is once again bathed in blue.

Apparently she wasn’t paying attention to her Science teachers because she has no explanation for why something that is clear in a drinking glass appears blue in a lake or sea.

Something or other about reflecting the sky?

But if water is blue because it reflects the sky above, how/where does the sky get its color from? I mean, isn’t it just . . . space?

By the way, this was a long time before Google existed. Now, of course, a few keystrokes and I have my answer:

Blue light is scattered in all directions by the tiny molecules of air in Earth’s atmosphere. Blue is scattered more than other colors because it travels as shorter, smaller waves. This is why we see a blue sky most of the time.Why not just ask the original question: Why does water look blue?

Blue wavelengths are absorbed the least by the deep ocean water and are scattered and reflected back to the observer’s eye. Particles in the water may help to reflect blue light. The ocean reflects the blue sky. Most of the time the ocean appears to be blue because this is the color our eyes see.

Okay. So there are particles and molecules and reflections and stuff and our eyes see the color blue when we look at water.

Some of the time.

The particular body of water and how close or far we are from the water also makes a difference.

If you’re painting a small stream in the mountains, surrounded by tall pine trees, would the water be blue or green?

Or both?

I chose to make this one dark green with a little brown and grey to represent the rocks beneath the water’s surface. The dark green is from the reflection of the timbers.

To be honest, when I painted this mural I had no idea about molecules and the rest of it. I actually had no idea until just right now when I googled those two questions. It would’ve made painting water so much easier had I done a little research.

But we don’t paint to learn the scientific basis of subject matter. We paint to . . . well, I don’t know why you paint. I paint to create and express myself.

And to discover.

In fact, discovery might be my primary joy. Even after all of these years, I love discovering how colors work together, how certain strokes create certain affects, how water isn’t always blue.

I’m not going to google why moving water with ripples is white.

But you’re certainly welcome to.

Over the years I learned a few things about painting water. Not a lot. A little.

I can look at my earlier works in the ’90’s and see how ‘blue’ all of my water paintings were. Even with loads of waves. For this mural above, the client wanted a stormy sea. If I were painting it now, it would be full of greys with barely any blue at all.

Oh well. She doesn’t live in this house here anyway. She divorced her husband and moved to Washington a number of years ago.

Now that would be an interesting piece – find out what has happened to all of the people who I painted murals for, if they still live in the house or where. Goodness, that’d take forever! I’ve painted a lot of murals over the years.

While this hanging canvas has a variety of color in the water, it was only because I painted from a photo the clients had.

I think painting from photo references is one of the best ways to learn how to paint. Particularly water. You start out just copying what your eye sees in the picture but eventually, with practice and time, you do learn how water flows and how to replicate that with your paintbrush.

A lot of times you only need a suggestion for water. Especially for wall murals that cover an expansive space.

In this photo the water looks like blue blotches, doesn’t it?

Stand back in the room a bit and it makes a bit more sense.

I should also say that this safari mural was painted for a baby boy and the parents wanted very soft, muted tones in the room.

I think it’s still one of my all-time favorite rooms I painted, just because I painted all four walls with all sorts of animals that Jett, the little boy, took delight in discovering as he grew.

But they no longer live there either. sigh. What’s even worse is I painted a cherry blossom mural in Jett’s baby sister’s room a few months before they moved.

I always try to get clients to have murals painted on canvas for this very reason. But most want it painted on walls. Oh well. I don’t paint murals anymore anyway.

I think the last mural I painted happened to have water in it though.

This was a bit of a challenge in that the room itself was a rotunda – a round room.

The water didn’t pose an issue, it was achieving perspective with curved walls.

Other than some ripples around the ducks, most of the water was just color blocking.

With only a smidgen of blue.

Yes, I still see blue when I look at water. But I also see white and grey and green and brown and turquoise and . . .

I still get a little timid when I have to paint water, but not nearly as much as I used to. For one thing, I do a lot of research.

That’s something I just realized, writing this.

I spend a long time, possibly hours, before painting even the simplest piece. (Especially water!) But even if someone has sent me photos of their pet, I spend time looking at photos online of that breed, it’s markings, musculature, etc.

I guess that would be my ‘tip’ for painting water – study it. Look at photos. Paint some. Look at more photos and then paint some more.

But mostly – and always – have fun!

Colleen

This was a very informative blog post. I liked how you had different examples. Excellent and beautiful work as well.